Recommender systems with Python - (2) What is collaborative filtering?

14 Jul 2020 | Python Recommender systems Collaborative filteringMost recommendation engines can be classified into either (1) collaborative filtering (CF) system, (2) content-based (CB) system, or (3) hybrid of the two. In the previous posting, we went through the concepts of the three and differences. To give you a little re-cap, content-based systems recommend items that are close to the items that the user liked before. For example, if I liked the movie Iron Man, it is likely that I will also like the movie Avengers, which is common-sensically similar to Iron Man. In contrast, CF systems suggest items that similar users liked, i.e., “people-to-people” correlation. In general, there are two steps in CF - (1) identifying users with similar likings in the past and (2) recommending items that such users prefer.

In this posting, let’s look into the details of CF.

Pros and cons of CF recommender systems

As described in the earlier posting, CB and CF approaches have their own advantages and disadvantages - they are more like the two sides of a coin. So to talk about the pros of CF, it would be better to start with the shortcomings of the CB approach. One of the main limitations of applying the CB approach to practical recommendation problems is the unavailability of content data. In many cases, it is difficult to obtain content information pertaining to all items of interest. For instance, how would you (numerically) describe the content of rock ‘n’ roll songs? In other words, how can you measure the (dis)similarity of two arbitrary songs, say Led Zepplin’s Stairway to heaven and Deep purple’s Smoke on the water?

Maybe we can try very simple features such as the duration of the song and which musical instruments are played? But this does not necessarily contain the “content” information of the song. How about more descriptive ones such as lyrics as text information? Then, can would you handle subtle information hidden in the context such as euphemisms and metaphors? Things often get easily complicated in the problem space of CB systems. Thus, the CF method bypasses these problems by ignoring the explicit content information and indirectly model them based on users’ past history. Therefore, one critical assumption of the CF method is that the users’ preference is relatively stationary over time. Furthermore, the user’s preferences are similar between a group of like-minded users, but differs between different user groups. For example, there should be some “collaborating” patterns that are time-invariant such as “users who like Beatles also like Nirvana.” If these assumptions do not hold, CF models are most likely to fail.

Another disadvantage of CB is that the method is highly domain-dependent. Let us assume that you found a feature extraction method to neatly analyze the music notes and lyrics of rock ‘n’ roll songs. Would that method apply to movie recommendation? What about restaurant recommendation? In practice, it is hardly possible to find a single CB method that works great in more than one domain. In contrast, CF is highly applicable since it relies on only user-item interaction patterns.

At the same time, CF is not applicable at all when user-item interaction patterns are non-existent. This is termed the “cold-start problem” since recommendations have to be made with a cold start, i.e., without sufficient information. Cold-start problems can arise in various scenarios. When we have a small amount of user-item interaction data or no significant findings can be inferred from the data, we have a general cold-start problem. However, there can be cold-start problems even when we have a large amount of training data and inferred patterns. For example, a new item does not have any interaction record with users is very difficult to be recommended. This is usually called the item cold-start problem. Problems for new users are, naturally, the user cold-start problem.

Memory-based CF systems

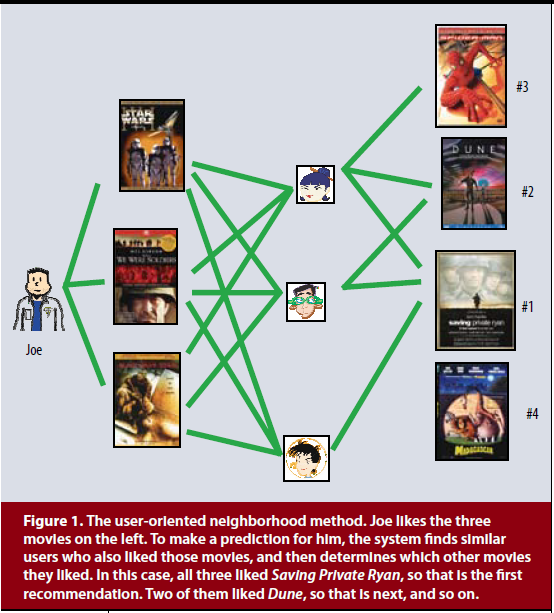

There are largely two branches of CF. The memory-based (aka heuristic-based or neighborhood) approach utilizes pre-computed user-item rating records, i.e., “memory,” to infer ratings for other items that the user has not encountered yet. In the abstract, the closest items to a certain user according to some metrics are recommended to that user, thereby having an alternative name of “neighborhood methods.” Then, the problem boils down to how to define and measure the concept of “closeness,” or “proximity” in the user and item space. After that, what is left to do is just picking the closest ones to the user.

Advantages of memory-based methods include, but are not limited to:

- Simplicity: intuitive and simple to implement.

- Justifiability: results are interpretable and the reasons for recommendation can be inferred by examining neighbors in most cases.

- Efficiency: does not require large-scale model training and neighbors can be pre-computed and stored.

- Stability: less affected by the addition of users, items, and ratings.

There are two methods to implement memory-based CF systems - (1) user-based and (2) item-based. The user-based approach first finds similar users to a user of interest, i.e., neighbors. Then, the rating for a new item is inferred based on rating patterns of the neighbors. In contrast, the rating for an item is predicted with ratings of the user for items that are similar to the item of interest. We will see how these two approaches differ in detail in the next postings.

Model-based CF systems

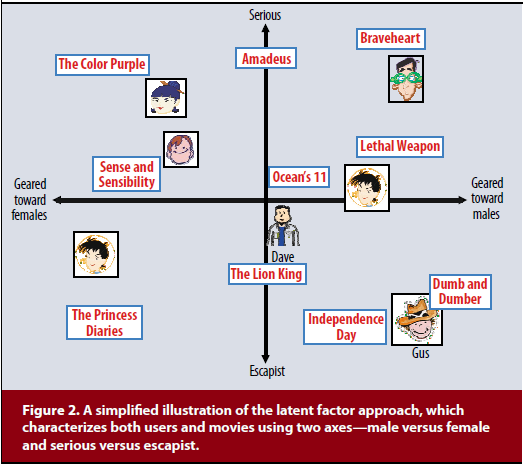

Model-based CF systems use various predictive models to estimate the ratings for a certain user-item pair. A wide variety of models are used in practice for estimation. One of the most salient family of methods is latent factor models that attempts to characterize both items and users with a finite number of latent factors. Matrix factorization is one of the most established methods for such approach. We will also discuss this in later postings.

References

- Ricci, F., Rokach, L., & Shapira, B. (2011). Introduction to recommender systems handbook. In Recommender systems handbook (pp. 1-35). Springer, Boston, MA.

- Gomez-Uribe, C. A., & Hunt, N. (2015). The netflix recommender system: Algorithms, business value, and innovation. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems (TMIS), 6(4), 1-19.

- Koren, Y., Bell, R., & Volinsky, C. (2009). Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. Computer, 42(8), 30-37.