Recommender systems with Python - (9) Memory-based collaborative filtering - 6 (k-NN with Surprise)

07 Sep 2020 | Python Recommender systems Collaborative filteringIn the previous posting, we implemented our first memory-based collaborative filtering system using theSurprise package in Python. In this posting, let’s see how we can improve the baseline k-NN model and try them to actually enhance the model’s performance on the MovieLens dataset.

Preparation

Prior to implementing the models, we need to install the Surprise package (if not installed already) and import it. For more information on installing and importing the Surprise package, please refer to this tutorial

from surprise import Dataset

from surprise import KNNBasic, BaselineOnly, KNNWithMeans,KNNWithZScore, KNNBaseline

from surprise.model_selection import cross_validate

Load a built-in dataset

Let’s start with loading a built-in dataset. Again, let’s use the MovieLens dataset. For more details about the data, please refer to the previous postings.

dataset = Dataset.load_builtin()

Training & evaluation

Changing the number of neighbors (k)

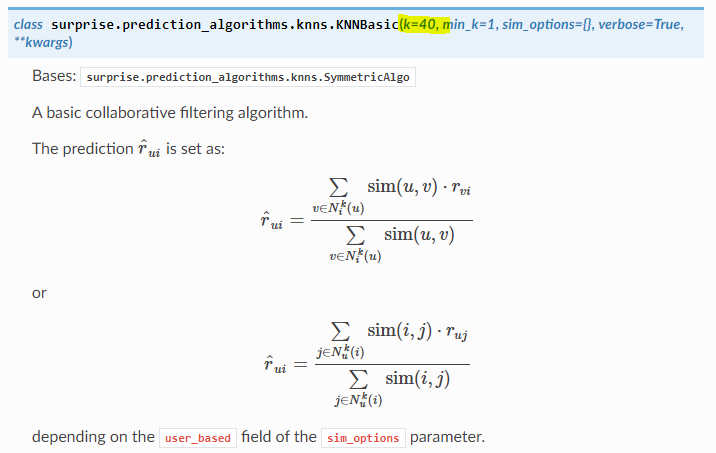

Any variant k-NN algorithm involves aggregating information pertaining to a pre-defined number of neighbors. The notation for that pre-defined number is k. Hence, k is one of hyperparameters that can potentially influence performance of the machine learning model.

The default value of k is 40 for k-NN-inspired algorithms in Surprise. However, this number can be further fine-tuned for optimal performance. There is no one-size-fits-all solution for k, so it is recommended to find an optimal one with search schemes such as random search and grid search (Bergstra and Bengio 2012). Here, let’s try different values of from 10 to 100 and compare the results.

sim_options = {

'name': 'MSD',

'user_based': 'True'

}

cv_results = []

for k in range(1, 11):

clf = KNNBasic(k= k*10, sim_options = sim_options)

cv_results.append(cross_validate(clf, dataset, measures=['MAE'], cv=5, verbose=False))

for i in range(10):

print("Average MAE for k = {} ".format((i+1)*10), cv_results[i]["test_mae"].mean())

It seems that setting k to around 30 yields relatively superior performance. However, differences in performances are not dramatic - we need other improvements to beat the baseline!

Average MAE for k = 10 0.7791384730857354

Average MAE for k = 20 0.7700308569739284

Average MAE for k = 30 0.770853160085353

Average MAE for k = 40 0.7729402525558153

Average MAE for k = 50 0.7756380474579305

Average MAE for k = 60 0.7774398619226626

Average MAE for k = 70 0.7807832701921905

Average MAE for k = 80 0.7821534570601616

Average MAE for k = 90 0.7850191446196909

Average MAE for k = 100 0.7856976099341807

Rating centering and normalization

Mean centering and normalization is a widely used feature transformation method in machine learning. In the recommendation context, the two methods convert individual ratings into a universal scailng. Even though we give the same ratings scale, e.g., 1-5 scale, how users perceive the absolute numbers in the scale can vary significantly. For instance, some users might be relatively “hard to please” compared to other users. Those users will consistently give lower ratings to most of the items that they have encountered. Therefore, mean centering subtracts the average of ratings that given by the user to every rating that the user has given. In addition, the Z-score normalization scheme considers “the spread” in the user’s rating scale.

The normalization can be conveniently implemented by using KNNWithZScore() instead of KNNBasic. It seems that the normalization yields a better performance, showing average test MAE of under 0.75. However, unfortunately, this is still not so satisfactory - the baseline estimator achieves similar performance.

sim_options = {

'name': 'MSD',

'user_based': 'True'

}

clf = KNNWithZScore(k=30, sim_options = sim_options)

cross_validate(clf, dataset, measures=['MAE'], cv=5, verbose=True)

Fold 1 Fold 2 Fold 3 Fold 4 Fold 5 Mean Std

MAE (testset) 0.7465 0.7479 0.7526 0.7455 0.7501 0.7485 0.0025

Fit time 0.47 0.49 0.48 0.48 0.48 0.48 0.01

Test time 3.55 3.48 3.57 3.50 3.62 3.55 0.05

{'fit_time': (0.4673135280609131,

0.486081600189209,

0.48402929306030273,

0.4768378734588623,

0.48423147201538086),

'test_mae': array([0.7464836 , 0.74794443, 0.75256676, 0.74552251, 0.75010478]),

'test_time': (3.545177936553955,

3.4846949577331543,

3.5715558528900146,

3.503652572631836,

3.6209750175476074)}

Incorporating baseline estimates

Finally, we can consider incorporating baseline estimates. Essentially, this is combining the baseline estimator and k-NN in a single algorithm. The motivation behind this is similar to mean-centering. But here, the biases present in user- and item-levels, i.e., user and item effects, are simultaneously considered and estimated.

“For example, suppose that we want a baseline estimate for the rating of the movie Titanic by user Joe. Now, say that the average rating over all movies, $\mu$, is 3.7 stars. Furthermore, Titanic is better than an average movie, so it tends to be rated 0.5 stars above the average. On the other hand, Joe is a critical user, who tends to rate 0.3 stars lower than the average. Thus, the baseline estimate for Titanic’s rating by Joe would be 3.9 stars by calculating 3.7 − 0.3 + 0.5.” (Koren 2010)

The KNNBaseline() implements such model - the usage is identical to other k-NN models.

sim_options = {

'name': 'MSD',

'user_based': 'True'

}

clf = KNNBaseline(k=30, sim_options = sim_options)

cross_validate(clf, dataset, measures=['MAE'], cv=5, verbose=True)

The k-NN model with baseline estimates show test MAE of around 0.73. Finally, we were able to get a significant improvement over the vanilla k-NN and baseline model!

Fold 1 Fold 2 Fold 3 Fold 4 Fold 5 Mean Std

MAE (testset) 0.7349 0.7325 0.7333 0.7291 0.7370 0.7334 0.0026

Fit time 0.63 0.66 0.67 0.66 0.67 0.66 0.02

Test time 3.68 3.81 3.76 3.76 3.73 3.75 0.04

{'fit_time': (0.6288163661956787,

0.6560549736022949,

0.6707336902618408,

0.6592440605163574,

0.6749463081359863),

'test_mae': array([0.73487928, 0.73254759, 0.73325744, 0.72909275, 0.73704706]),

'test_time': (3.682957410812378,

3.811162233352661,

3.7631664276123047,

3.7610509395599365,

3.7297961711883545)}

In this posting, we tried different schemes to improve the baseline estimator and vanilla k-NN. On top of these, there are of course many other ways to improve the model, including data processing and fine-tuning the hyperparamters. Let me know if you find better ways!

References

- Bergstra, J., & Bengio, Y. (2012). Random search for hyper-parameter optimization. The Journal of Machine Learning Research, 13(1), 281-305.

- Koren, Y. (2010). Factor in the neighbors: Scalable and accurate collaborative filtering. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data (TKDD), 4(1), 1-24.

- Ricci, F., Rokach, L., & Shapira, B. (2011). Introduction to recommender systems handbook. In Recommender systems handbook (pp. 1-35). Springer, Boston, MA.