Recommender systems with Python - (4) Memory-based collaborative filtering - 1

19 Jul 2020 | Python Recommender systems Collaborative filteringSo far, we have broadly reviewed the recommender systems and collaborative filtering (CF) field. Now, let’s narrow down a bit and look into the memory-based (or neighborhood/heuristic) methods. As explained in the previous posting, memory-based CF systems use simple heuristic functions to infer ratings for prospective user-item interactions using previous rating records. Therefore, they have advantanges such as simplicity, justifiability, efficiency, and stability. In this posting, let’s try intuitive understanding of the CF methods.

Intuitive understanding of memory-based CF

In many cases, the naming of the method reveals many characteristics of the method. Therefore, even though we do not know the details of the memory-based CF systems, we can try to understand it by examining the alternative names like blind men groping elephants.

Memory

As the name suggests, memory-based CF primarily relies on “memories” of user-item interactions. However, this statement might be misleading at the first glance, since virtually every CF methods should memorize some patterns of such interactions to make inferences later. To make this more sense, we can introduce a contrastive concept of “generalization.”

[Photo by Fredy Jacob on Unsplash]

[Photo by Fredy Jacob on Unsplash]

To start with, memorization is concerned with explicit co-occurrence or correlation patterns present in previous data. In general, those patterns can be expressed in simple decision rules such as IF-THEN. For example, “if the user liked the movie Star Wars, he/she will like the movie Pulp Fiction.” Those patterns can be easily recognized and memorized.

“Memorization can be loosely defined as learning the frequent co-occurrence of items or features and exploiting the correlation available in the historical data.” (Cheng et al. 2016)

However, in many cases, human behavior is complicated than that. For instance, even though the likings of Star Wars and Pulp Fiction are correlated, there might be other moderating/mediating variables. It might be the case that many users who like Star Wars like the movie Fight Club and those who like Fight Club like Pulp Fiction. In fact, most users who like Star Wars and do not like Fight Club might dislike Pulp Fiction. Furthermore, with the number of items and users getting astronomically big in many practical applications nowadays, the problem space gets infinitely convoluted. Those patterns are difficult not only to elucidate, but also to memorize them. Thus, many recent methods such as embedding-based ones attempt to achieve generalize such patterns in a high-dimensional latent space.

“Generalization, on the other hand, is based on transitivity of correlation and explores new feature combinations that have never or rarely occurred in the past.” (Cheng et al. 2016)

[Photo by Maxime VALCARCE on Unsplash]

[Photo by Maxime VALCARCE on Unsplash]

There is a fine line between memorization and generalization. However, the general rule of thumb is that if “I know it when I see” the pattern, it is likely to be a memorizable pattern. Cheng et al. (2016) provide more in-depth discussions on generalization and memorization in describing their Wide & Deep learning framework.

Heuristic

Now we now that memory-based CF systems in general relies on memorizing straightforward patterns in data. Besides, they are heuristic methods that exploit simple, memorizable patterns in previous data. This characteristic makes the method heavily rely on rules of thumbs derived from in-depth domain knowledge.

The central concept of memory-based methods is the notion of similarity, or closeness between items and users. Based on pre-defined metrics for similarity or proximity, major tasks in recommender systems such as top-K items recommendation or ratings prediction can be carried out. However, though it may sound straightforward, methodically defining similarity and quantifying it is not so simple and quick. For instance, how would you measure the similarity between movies Fight Club and Pulp Fiction? How would they compare to the similarity between Fight Club and Star Wars? From the user’s perspective, if Peter and Jane both loves Star Wars, and Peter likes Pulp Fiction but Jane hates Pulp Fiction. Would you regard that those two users are similar or dissimilar?

Furthermore, even though after we decide how to measure the similarity between users and items, how can we use them to make a decision and actually recommend items to users? To investigate the similarity measure deeper, we need to understand the concept of neighborhood.

Neighborhood

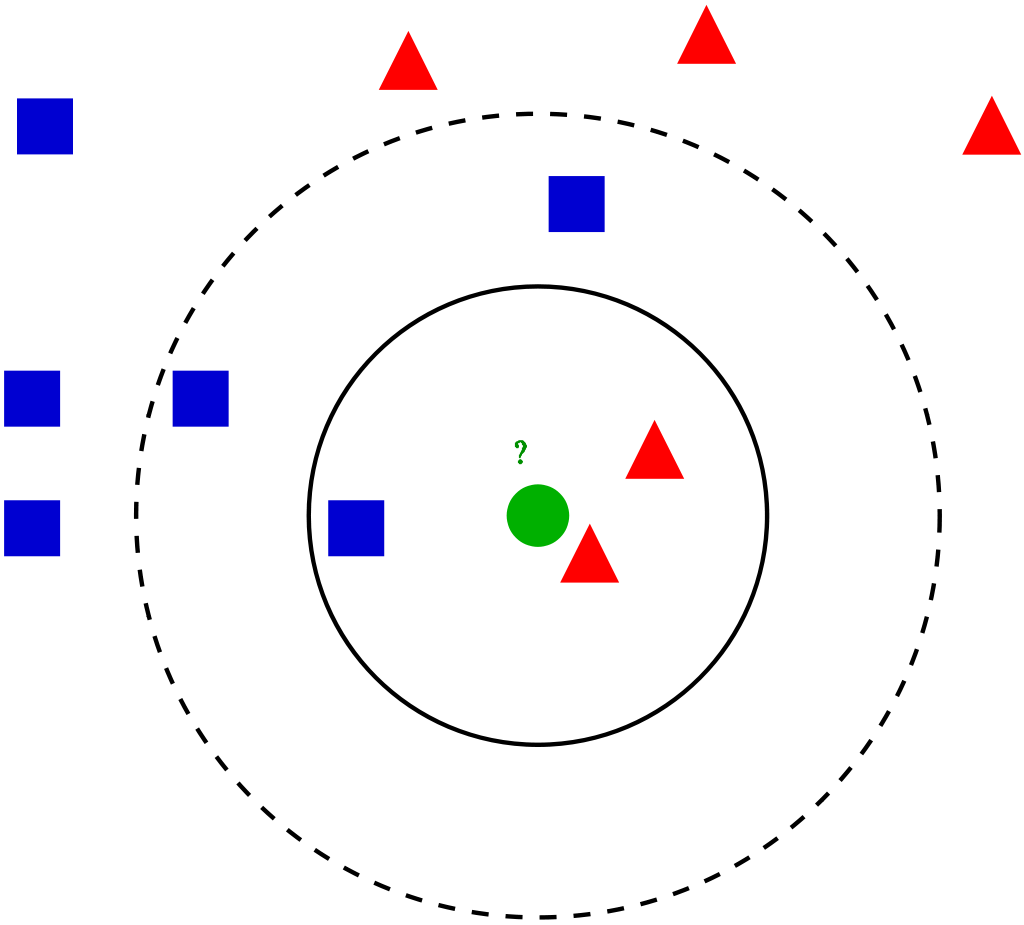

Memory-based methods borrow intuition from the k-neareast neighbors (k-NN) algorithm in pattern recognition. In the abstract, k-NN assigns a value to an instance of interest by averaging the values of neighbors that are close to the instance, i.e., neareast neighbors. k-NN can be used for both classification and regression tasks.

[ Image source]

[ Image source]

In the recommender systems context, we have two types of instances - users and items. Accordingly, nearest neighbors can be identified in both types of instances and inferences can be made in both ways. Therefore, we have two branches of memory-based methods - i.e., user-based and item-based. Assume that we want to predict the rating for the movie Fight Club by John, who hasn’t watched the movie yet. Then, the two methods carries out the same task slightly differently as follows.

-

User-based methods: guess future rating for Fight Club by John using the ratings to Fight Club by Casey, Sean, and Mike who have similar likings to John.

-

Item-based methods: guess future rating for Fight Club by John using the ratings to Star Wars and Pulp Fiction, which are similar items to Fight Club, by John.

I delibrately avoided the usage of rigorous definitions and mathematical details since I wanted to provide an “intuitive understanding” in this posting. From the next posting, let’s see how the two methods for memory-based CF are defined rigorously and (relatively easily) implemented in Python.

References

- Ricci, F., Rokach, L., & Shapira, B. (2011). Introduction to recommender systems handbook. In Recommender systems handbook (pp. 1-35). Springer, Boston, MA.

- Cheng, H. T., Koc, L., Harmsen, J., Shaked, T., Chandra, T., Aradhye, H., … & Anil, R. (2016, September). Wide & deep learning for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 1st workshop on deep learning for recommender systems (pp. 7-10).

- Koren, Y., Bell, R., & Volinsky, C. (2009). Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. Computer, 42(8), 30-37.

[

[