The Netflix Challenge - Collaborative filtering with Python 11

21 Sep 2020 | Python Recommender systems Collaborative filteringIn the previous posting, we overviewed model-based collaborative filtering. Now, let’s dig deeper into the Matrix Factorization (MF), which is by far the most widely known method in model-based recommender systems (or maybe collaborative filtering in general). Before that, it is helpful to be a little bit knowledgeable of the Netflix Prize in 2009. Why? You will get to know after you read this article.

Netflix Prize challenge

The Netflix Prize was an open challenge closed in 2009 to find a recommender algorithm that can improve Netflix’s existing recommender system. Netflix, like many other information technology companies nowadays, creates tremendous economic value from its recommender system. It has been reported that about 80% of user choices of Netflix videos are attributable to personalized recommendations (Gomez-Uribe and Hunt 2015).

The Netflix Prize provided the data and incentives for researchers that led to major improvements in applying matrix factorization methods to recommender systems. Matrix decomposition methods such as singular value decomposition were proposed much earlier, but it was during and after the Prize that variants of such methods were increasingly applied and dramatically ameliorated for collaborative filtering.

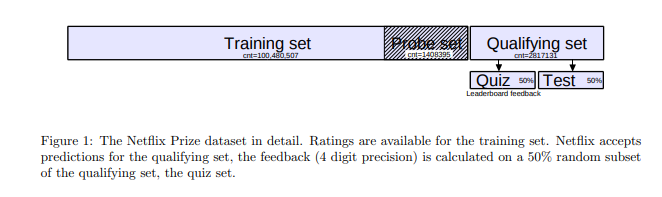

Dataset

The dataset includes 5-star rating records on 17,770 movies and 480,189 users. The total number of ratings was 100,480,507, which includes the “probe set” of 1,408,395 ratings to validate the performance. Finally, there is a qualifying set of size 2,817,131. The objective is to achieve a root mean squared error (RMSE) under 0.8563 on the “Quiz subset” of the qualifying set. Finally, the Grand Prize is given to the team with the lowest RMSE score on the remaining ratings in the qualifying set, i.e., “test set.” (Töscher et al. 2009)

Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems

At the end of the day, the team BellKor’s Pragmatic Chaos, which was a hybrid of two teams KorBell and Big Chaos, won the $1 million grand prize. KorBell, comprising researchers from AT&T, won the first Progress Prize milestone during the early stage of the challenge. Koren et al. (2009) published the article Matrix Factorization Techniques for Recommender Systems in IEEE Computer, summarizing state-of-the-art techniques in matrix factorization and how they can be applied for recommendation tasks in the wild.

However, the BellKor’s Pragmatic Chaos team not only utilizd matrix factorization methods but also blended diverse collaborative filtering algorithms including the Restricted Boltzmann Machine, k-Nearest Neighbors, and MF (Töscher et al. 2009). Furthermore, in fact, MF itself is not a single model, but a loose term to refer to latent models that represent user and items in a low-dimensional latent space. Moreover, with more and more researchers diving into the field, many variants of the initial MF algorithms have been proposed to accomodate for various issues in real-world recommendation tasks. For example, refer to Funk (2006), Koren (2008), and Zhang et al. (2006) for earlier models.

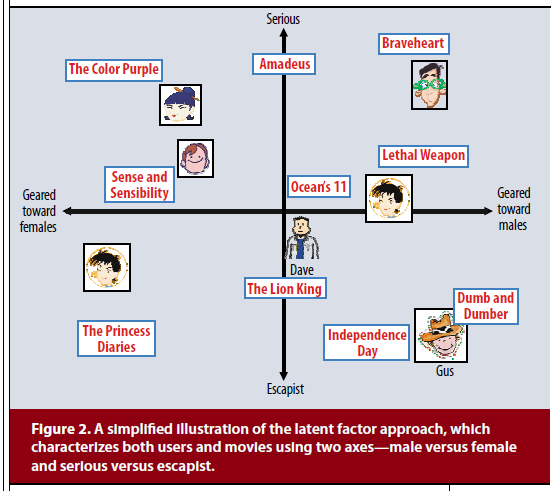

Nonetheless, most MF models and variants have common components, which are decomposing a (user-item interaction) matrix and learning the latent factors to describe users and items. The factors are like dimensions to measure the features of items or proclivity of users. In Figure 2 (Koren et al. 2009) below, the two factors (dimensions) describe masculinity/femininity (geared towards males/females) and seriousness (serious/escapist) of movies. Note that not only items (movies) but also users can be described in terms of combinations of factors based on their preference patterns.

Nevertheless, individual users’ preference patterns are much more complicated and sometimes inexplicable by nature. For example, Tony loves Mafia movies such as The Godfather, and Scarface, and Donnie Brasco in general. However, he does not like the actor Joe Pesci, making him dislike Mafia movies such as Casino, Goodfellas, and Irishman. In this case, should we encode Tony as liking Mafia movies or not? Should be create another factor having Joe Pesci-ness as a feature?

MF models do most of those dirty jobs for us. They inductively learn the factors and corresponding user/item representations by examining users’ interaction patterns. And this is the most imortant component of most MF algorithms. Various optimization schemes are used for such inference, differentiating many MF models from each other. From the following posting, let’s see how established MF models learn those patterns.

References

- Gomez-Uribe, C. A., & Hunt, N. (2015). The netflix recommender system: Algorithms, business value, and innovation. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems (TMIS), 6(4), 1-19.

- Funk, S. (2006) Netflix Update: Try This at Home. (https://sifter.org/~simon/journal/20061211.html)

- Koren, Y., Bell, R., & Volinsky, C. (2009). Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. Computer, 42(8), 30-37.

- Koren, Y. (2008, August). Factorization meets the neighborhood: a multifaceted collaborative filtering model. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining (pp. 426-434).

- Zhang, S., Wang, W., Ford, J., & Makedon, F. (2006, April). Learning from incomplete ratings using non-negative matrix factorization. In Proceedings of the 2006 SIAM international conference on data mining (pp. 549-553). Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

- Töscher, A., Jahrer, M., & Bell, R. M. (2009). The bigchaos solution to the netflix grand prize. Netflix prize documentation, 1-52.

- Ricci, F., Rokach, L., & Shapira, B. (2011). Introduction to recommender systems handbook. In Recommender systems handbook (pp. 1-35). Springer, Boston, MA.